Entries in Missing Reels (8)

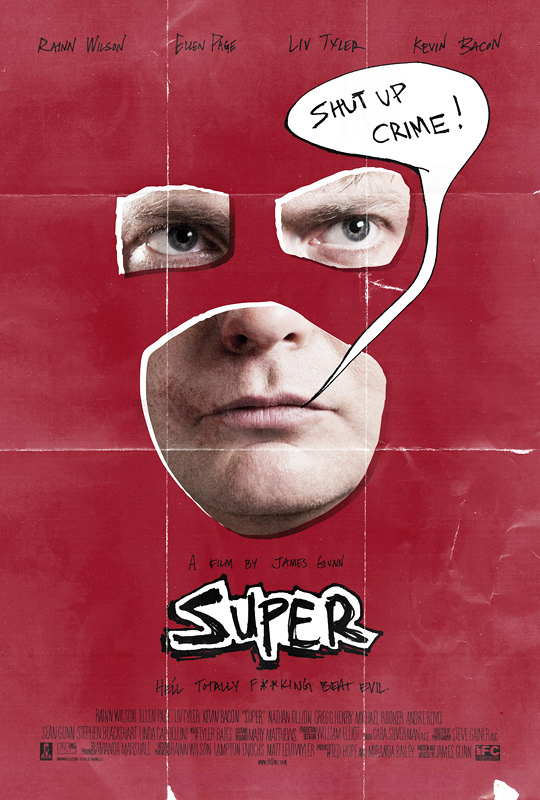

"Super" (2010)

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, August 18, 2011 at 12:45PM

Thursday, August 18, 2011 at 12:45PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

Sometimes it's easiest to tell the most personal stories - the ones that really lay bare your feelings - by disguising it behind something truly bizarre. If something is seen as weird or ridiculous, then it's easy to dismiss and thus easy for the storyteller to not be hurt by the criticisms. By dressing an intimate truth in the costume of the outrageous, it offers some shelter to the fragile psyche of the creator. After all, critics will go after the garish or surreal before addressing anything deeper or more profound in a work. It's easier, for critics, to deal with the superficial and the shallow, to tackle the obvious and overt, than it is to peer deeper into a work. To be fair to critics, deeper readings of films usually reveal a lack of depth and not a hidden profundity. Sometimes a tentacle is just a tentacle, or a headshot is just a headshot.

Sometimes it's easiest to tell the most personal stories - the ones that really lay bare your feelings - by disguising it behind something truly bizarre. If something is seen as weird or ridiculous, then it's easy to dismiss and thus easy for the storyteller to not be hurt by the criticisms. By dressing an intimate truth in the costume of the outrageous, it offers some shelter to the fragile psyche of the creator. After all, critics will go after the garish or surreal before addressing anything deeper or more profound in a work. It's easier, for critics, to deal with the superficial and the shallow, to tackle the obvious and overt, than it is to peer deeper into a work. To be fair to critics, deeper readings of films usually reveal a lack of depth and not a hidden profundity. Sometimes a tentacle is just a tentacle, or a headshot is just a headshot.

And so the time honored tradition of Trojan Horsing other layers in populist work. Take whatever is popular in mainstream entertainment and hit all the same notes, adhere to the formulas, while subtly slipping in breadcrumbs of your ulterior motive. Sometimes this technique is used for political purposes, other times it's a deconstruction of the entire genre. But, occasionally, it's a way for the artist to reveal something that would leave him ultimately vulnerable, except that it's done in a way that's easy to disavow. "I'm just telling a story of a guy fighting a three-headed alien - I don't see where you get all this 'father issue' stuff!"

Today's film, Super, told a very universal story with immensely personal elements all wrapped up in a genre fare that could be dismissed by naysayers as ultraviolent or "just another superhero flick." Super is a fun flick that has some great scenes of action, lots of WTF moments and great comedy. But, as I was watching it, I couldn't help but sense that something else was going on - there was another layer to this whole story that seemed to be occurring just beneath the surface. The movie ended and I took to the interwebs and found Devin Faraci's excellent review. It was well written and the only one that I could see that openly dealt with what I thought this movie was about: dealing with a devastating break-up.

Redbelt

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, July 7, 2011 at 3:00PM

Thursday, July 7, 2011 at 3:00PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

"The hands are not the issue. The fight is the issue. The battle is the issue. Who imposes the terms of the battle will impose the terms of the peace. Think he has a handicap? No. The other guy has a handicap if he cannot control himself. You control yourself, you control him."

"The hands are not the issue. The fight is the issue. The battle is the issue. Who imposes the terms of the battle will impose the terms of the peace. Think he has a handicap? No. The other guy has a handicap if he cannot control himself. You control yourself, you control him."

We are at a point of divergence in the history of action movies - it's happened previously, where two philosophies are diametrically opposed and stand in stark contrast with each other. One is the more popular, socially acceptable version that is equated with money, gloss and mindless fun that is represented by Hollywood. The other is more associated with smaller films, critical acceptance, international audiences and a lack of funds that is offset by a display of skill. I'm talking about Explosions vs. Fights.

Please note - these are overarching terms meant to reductively label two mindsets. They are not mutually exclusive, per se, nor fully descriptive of the issues at hand. But, for the purposes of this discussion, it's easiest to separate these two worlds using these (notably obsolete) words.

The School of Explosions is presided over by Jerry Bruckheimer and Michael Bay - it's the world of the flashy spectacle where excess is encouraged and there is no gesture considered "too broad" or an action setpiece that can be seen as "too convoluted." A reliance on celebrities, pretty people, and CGI, films made in the School of Explosions are geared towards ADHD addled audiences more interested in seeing something cool than seeing something that makes sense - even using the shaky internal logic of the movie itself.

Murder Party

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, June 30, 2011 at 1:00PM

Thursday, June 30, 2011 at 1:00PM  Horror films are the basis for my love of movies.

Horror films are the basis for my love of movies.

Firstly, as verboten pieces of art that I was discouraged from viewing as a child because they would give me nightmares or because they were 'trash,' horror films transformed from merely objects of entertainment into forbidden slices of escapism that I needed to learn about, watch, experience and absorb. Horror movies were something secretive that held power over others (particularly authority figures) and yet were looked down on and derided as filth. This dichotomy spurred me to learn more about each of the films, watch more of them and, in turn, learn more about film in general. In an effort to claim some of that power or unravel that mystery, I exposed myself to hours and hours of film, I had no choice but to fall in love with the medium.

Secondly, within the broad genre of horror, films run a large gamut of subgenres and sub-classifications: comedies, science fiction, trash, action, social/political commentary, exploitative. There's no "one type of horror film" - there are schools of thought and approaches but no unifying element that makes something a horror film. Horror movies can be scary, or gross, or gory, or funny, or sexy or chilling or all of the above. Horror movies tend to hinge on tone, an intangible element that tends to be signature of the auteur/director behind the film. Even if films share the same general plot points, it's the injection of tone and realization of the filmmakers' vision that defines each movie. So while consuming all of these horror movies, growing to love film, I also began to understand the subtle (and not so subtle) differences between genres, tones and executions of material.

Thirdly, watching mass quantities of horror movies leads to appreciating good elements of movies, if only to preserve one's sanity. Maybe Hell Comes to Frogtown is a crap film (it is), but you can appreciate the humor of the Lady Frog trying to sex "Rowdy" Roddy Piper. Or maybe The Quest (a/k/a Frog Dreaming) is a terrible movie (it is), but it has haunting shots and scenes that have stayed with me for multiple decades. The gore effects of Nightmare on Elm Street IV: The Dream Master, the quips of Friday the 13th VI: Jason Lives, the badassery of Phantasm II, the creature design of Nightbreed - every film, no matter its overall merits, has at least one element or scene that is appealing and well done. Even if, during those awkward pubescent years, those elements tend to be boob-related. Horror movie fans can sift through hours of crap to find something that made those hours worthwhile. And if a film has more than 1 or 2 elements that are good? An interesting score AND amazing tits? Well then the road to understanding what makes a good film (outside of aforementioned tits) begins as disparate pieces come together to make a strong, unified whole that is then spread through proselytizing to other nerds. "You haven't seen Evil Dead II? Oh we are having a sleepover and watching that RIGHT NOW!"

There are other examples of how horror movies play such pivotal roles in the formation of film freaks, many of them covered in this piece by Devin Faraci, but the point is that for such an easily vilified, belittled and ghettoized genre - horror films can serve as introduction to a love of cinema due to its broad range and malleability. Which brings us to today's film, 2007's Murder Party, written and directed by Jeremy Saulnier, a dark comic Halloween film that is as steeped in film geekery as it is in obscurity.

No Post Today

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, June 23, 2011 at 2:00PM

Thursday, June 23, 2011 at 2:00PM

Sorry, folks. I feel like absolute shit and am having problems looking at the screen. Everything else will continue as scheduled and I'll put up 2 "Missing Reels" columns next week.

I know, Bunk; I'm disappointed, too.

The Return of Captain Invincible

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, June 16, 2011 at 12:30PM

Thursday, June 16, 2011 at 12:30PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

What I want to bring back to superheroes with this project is a sense of play. Things have gotten so dreary. The heroes have gotten so ugly that even their muscles have muscles.

What I want to bring back to superheroes with this project is a sense of play. Things have gotten so dreary. The heroes have gotten so ugly that even their muscles have muscles.

- Frank Miller

Ignorance is bliss. Sure, it's "better" to know the truth - but it's not always a good feeling. Here's an example: you know the song "Brown Eyed Girl" by Van Morrison? It's a sweet summer song of days gone by, right? It's about anal sex. Just listen to the lyrics: "Behind the stadium...down in the hollow...playing a new game..." Clearly it's about that special bond between a man and the first girl who lets him do it in the butt.

Or maybe it's not. This is a brilliant and hilarious thought exercise put forth by Shannon Wheeler in Too Much Coffee Man: now that you've just been exposed to this piece of information - you will always associate "Brown Eyed Girl" with butt sex. Even though things may not be true, certain bits of knowledge can never be unlearned.

Today's movie isn't about butt sex (not that I noticed, anyways) but it is about the fallacy of nostalgia. It centers on that lie put forth by regressives that, at one point in the past, there were "golden days." Don't get me wrong - there were definitely years for America that were objectively better than this current age of horrible new diseases, rampant pollution, erratic natural disasters, catastrophic economic woes. But to say that "times were better" is to imply a giant asterisk: yes, times were better if you were a white American man above a certain level of wealth. The Post-World War II era was a prosperous one for the US - but mainly due to the fact that every other country had been utterly decimated by war, bombing campaigns and more war. And sure, maybe the truthiness of growing up in the 50s was that everything felt better - but that's because people weren't informed about all the various levels of corruption in politics, pollution in the environment, exploitation of other countries, carcinogens in household items, etc.

Times were better - because most people didn't know any better. The deluge of information brought along the weariness of cynicism - but also the responsibility of knowledge. Armed with knowing as many facts about a situation as possible, the hope is that people can make informed decisions that are based on rational deliberation and not ignorance or fear. Of course, that doesn't always pan out, but the theory is sound.

But what does this all have to do with an Australian superhero parody from 1984? The Return of Captain Invincible is about an American, patriotic costumed do-gooder who went from being the beloved hero of a nation to becoming a forgotten footnote delegated to the alleyways of Australia. Alan Arkin plays the recovering alcoholic Captain Invincible, a man formerly ensconced in the flag but now lying in a puddle of his own filth. Oh...and it's a musical.

Feeding Frenzy

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, June 9, 2011 at 12:48PM

Thursday, June 9, 2011 at 12:48PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

The dilemma of the critic has always been that if he knows enough to speak with authority, he knows too much to speak with detachment.

The dilemma of the critic has always been that if he knows enough to speak with authority, he knows too much to speak with detachment.

- Raymond Chandler

You, the critic, the professional appreciator, putting something new into the world.

- High Fidelity

It would be easy to say that the one thing all great art has in common is that it is built on passion. In fact, I just said it. But, while I believe that's true, it sounds too facile, too simplistic. More over, it sounds like the problem with bad art is a lack of passion - when that's usually not the case. I would propose all great works of art are passionate projects of the artist but not all passionate projects of the artist are great works of art. Passion drives artists to realize their visions in their chosen medium - it's what makes them resolute despite the very real possibility that what they are working on is shit and that no one will even notice it let alone like it. Such cockeyed determination can be a good thing when the artist transcends convention and presents something new, something rewarding. Or it can be a bad thing when the artists are so insulated by sycophants and slavish devotion to their visions that they end up ignoring the reality of just how much their creation sucks.

Another hallmark of artists that has its share of positives and negatives is a deep knowledge and history of the art form within which they are working. Even if the artist's intent is to do something never seen before and completely revolutionize his medium - he has to know what has been seen before in order to be certain of his originality. Most successful artists have an extensive knowledge of everything that preceded them - it's how they're able to build on the shoulders of these giants, to make a name for themselves while acknowledging the history that led to this moment. It seems this has never been more evident than in film, first with the Film Brats (De Palma, Scorsese, Spielberg, Coppola) of the 70s who were raised on Hollywood and sought to invert expectations and then continuing on the tradition through to Tarantino, Takashi Miike and the Dogme 95 movement of the 90s and early 2000s. The idea of the critic, that person with an encyclopedic knowledge of something, becoming the artist - taking knowledge and turning it into action - is a long standing tradition with various degrees of success. Sometimes homages, mash-ups and revisions end up elevating the original works referenced while creating a unique entry that stands along side those classics. Sometimes they are nothing more than rip-offs built on a checklist of references and winks, missing the intangible soul and spark of originality that inspired the critic turned artist.

When these two aspects of artists collide to form the synthesis of the passionate critic as artist, it can be a thrilling thing to behold. For the most part, criticism offers the enticing proposition of safety - critics are reflecting on other people exposing their thoughts, not risking something wholly their own. So for a critic to shrug off the security of the peanut gallery and boldly hold themselves up for criticism by their former peers, it's a courageous feat that can be as awesome as it is painful. Feeding Frenzy (2010), comes from Red Letter Media, a group of people who became well known for their criticism but who displayed a level of passion that makes it easy to be charmed by the end result.

The Horseman

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 12:30PM

Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 12:30PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

Revenge is a confession of pain.

- Latin Proverb

In the 21st century, critics have lent more credence to revenge movies - positing that they're cathartic expressions for audience members who are unable to visit their anger on the various trespassers they believe worthy of such treatment. The driving force behind this sudden renewed bloodthirst was usually identified as the amorphous, generalized anger people felt in the wake of the terror attacks and subsequent wars beginning in 2001.

There was no clear cut "Us" vs. "Them," the definitions were more subtle and thus harder to picture and more difficult to envision fitting punishment. In essay after blog posting, critics posited that since the enemy was more an ill-defined idea ("Terror"), Americans (usually the driving force behind movie trends) needed villains with faces and, more importantly, needed to see these villains pay.

Personally? I think that's a load of shit. Not that Post-9/11 films weren't full of cathartic escapism where Liam Neeson or Denzel Washington slapped people around, or Jack Bauer used "enhanced interrogation methods" on his own brother. Of course that was catering to a collective unconscious need for such vindication, usually wrought in a very visceral and primal fashion. But I don't think that 9/11 is the root cause for revenge films' popularity.

The Theatre of Vengeance has been popular in the arts since the very beginning. Theatre of Vengeance is beyond international borders and cultural mores, pervading every medium and thriving in societies throughout history. The schadenfreude experienced by watching great kings undone by their own stupidity and hubris on stage (Shakespeare, Aristophanes, Sophocles, Goethe); the giddiness of readers exciting at the tales of a wronged man or men targeting their antagonists and ripping them asunder (The Count of Monte Cristo, The Iliad, Richard Stark's The Hunter); and the past century has brought us many classic tales of revenge writ large on the silver screen from Cape Fear to Get Carter to Enter the Dragon to Django to Kill Bill to Oldboy to today's entry, 2008's The Horseman. The tale as old as time isn't star-crossed lovers - it's the journey that begins with digging two graves and ends with both of them filled.

Missing Reels: Zero Effect

Rob Dean On

Rob Dean On  Thursday, May 26, 2011 at 2:00PM

Thursday, May 26, 2011 at 2:00PM Rob Dean examines the overlooked, unappreciated or unfairly maligned movies. Sometimes these films haven't been seen by anyone, and sometimes they've been seen by everyone - who loathed them. This is Missing Reels.

Today's film is the 1998 comic-neo-noir-detective-character-study Zero Effect. With an easy sell like that, how could it have not done well? Written and directed by Jake Kasdan (yes, son of Lawrence "I Wrote the Good Parts of Your Favorite Movies But Also Dreamcatcher" Kasdan), the film is a look at a quirky detective who's idiosyncratic approach to crime-solving makes him a very successful sleuth, but also marks him as an oddball outcast who is ill-equipped to deal with people. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Like the entire line up of USA programming from Monk onward?

Today's film is the 1998 comic-neo-noir-detective-character-study Zero Effect. With an easy sell like that, how could it have not done well? Written and directed by Jake Kasdan (yes, son of Lawrence "I Wrote the Good Parts of Your Favorite Movies But Also Dreamcatcher" Kasdan), the film is a look at a quirky detective who's idiosyncratic approach to crime-solving makes him a very successful sleuth, but also marks him as an oddball outcast who is ill-equipped to deal with people. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Like the entire line up of USA programming from Monk onward?

Well, apparently it was too ahead of its time as most people haven't seen it. Using IMDB's numbers, the budget was $5M and it only made about $2M in its theatrical run. People were not coming out to see "the world's most private detective." This is also due to how the film was marketed: a quirky comedy starring that guy from that show on Fox that no one saw but won an emmy, and all those other hilarious comedies!

Ultimately, it's a real shame that people haven't seen this film. Zero Effect is a good character study of people who set out to define their lives but ultimately are defined by outside forces. It's also a great updating of Sherlock Holmes, taking the obsessive, addict, musical and social malcontent elements and bringing them into late 90s America. And, lastly but not leastly, it's an interesting mystery movie that quickly solves the original mystery in favor of finding the deeper reasons and more profound secrets that are at work.